Object Oriented Programming using Python

Object Oriented Programming using Python

Classes and Objects

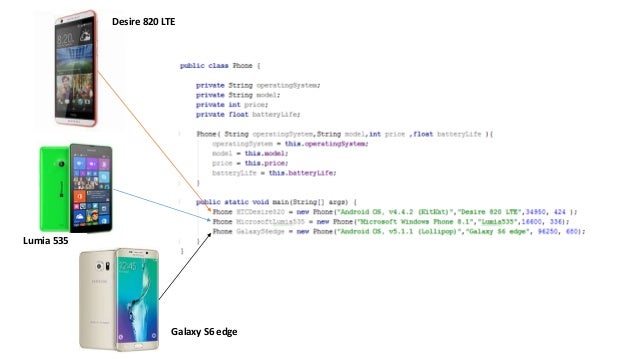

Let us start with a simple idea. Close your eyes. Imagine something! If you can identify what you imagined clearly then it is an object otherwise it is a class! Let us say that we imagined a picture of the phone. Now what phone was it? What were its features? We can say that a phone had the following features:

- Color

- Model

- Brand

- Screen Size

- Operating System And the phone had the following behavioural properties:

- Switch on

- Switch off

- Call

- Browse

Now, let us answer the questions one by one about what you imagined in the exercise!!

If I say that the phone I imagined was say white in colour, model X, brand Apple, with a screen size of say 6 inches, and an iOS operating system, I can easily identify it as iPhone X. While, if I am not able to answer any one of these features clearly, then it cannot be said to be a specific phone like iPhone. Thus, in this paradigm, iPhone X is an object and the phone is a class. Hence, an object can be simply defined as a real-time entity with properties and behaviour which belongs to a blueprint called class.

Similarly, we can imagine a class of Car as well!

It has the features of fuel, maximum speed, number of gears etc. and a simple behaviour of refuel, get fuel, set speed and drive! So, if we instantiate it to say Hyundai i10 then that instance is an object whose properties can be described by the class Car. Hence, a class is a concept to enable users to make their own data-type and gives more power to the programmer! SUDO (A programming paradigm for cheers ;) )!

Let us give a formal definition to class and object then!

It has the features of fuel, maximum speed, number of gears etc. and a simple behaviour of refuel, get fuel, set speed and drive! So, if we instantiate it to say Hyundai i10 then that instance is an object whose properties can be described by the class Car. Hence, a class is a concept to enable users to make their own data-type and gives more power to the programmer! SUDO (A programming paradigm for cheers ;) )!

Let us give a formal definition to class and object then!

Class: A user-defined blueprint or prototype of which objects are composed of, it represents the features, properties and behaviour common to all objects belonging to that paradigm.

Object: It refers to any real world entity which exhibits the following properties: State: Representation of attributes describing the object Behaviour: Representation of methods of an object Identity: Each object is assigned a unique name

In general, we practice a programming paradigm called procedural programming. In procedural programming, a program is divided into smaller parts called methods. These methods are the basic entities used to construct a program. One of the main advantages of procedural programming is code reusability. However, the implementation of a complex real-world scenario becomes a difficult task unwieldy.

The basic idea of OOP is to divide a sophisticated program into a bunch of objects talking to each other.

The concepts of objects and classes allow us to create complex applications in Python. This is why classes and objects are considered the basic building blocks behind all OOP’s principles.

- They are also instrumental for compartmentalizing code. Different components can become separate classes which would interact through interfaces. These ready-made components will also be available for use in future applications.

- The use of classes makes it easier to maintain the different parts of an application since it is easier to make changes in classes

Let us dive into a little bit of hands-on:

class firstClass:

pass

object = firstClass()

print(object)

I could have given a run option here, but left it intentional because it is highly encouraged that you learn to setup your Python Environment on local computer by simply searching the installation instruction steps as a self-assessment work out of interest.

So, as you can see it is a simple syntax compared to other programming languages, and Python makes it simpler to learn object oriented approach due to its inherent modularity.

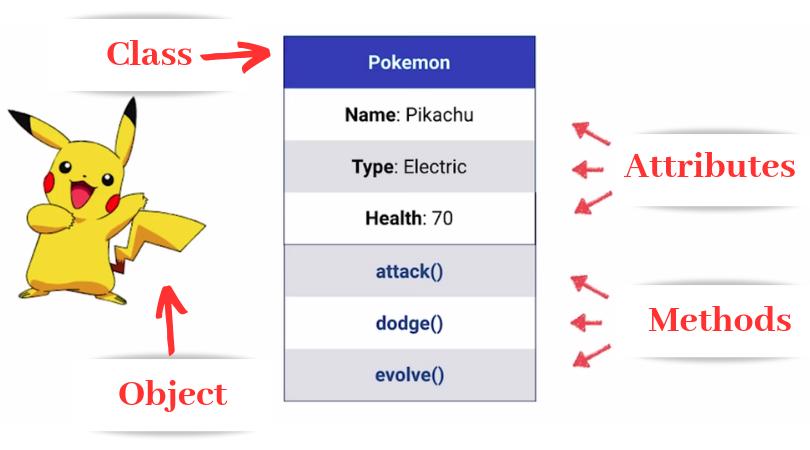

Say we want to implement the following class (borrowed from Medium):

class Pokemon:

def __init__(self, Name=None, Type=None, Health=None):

self.Name = Name

self.Type = Type

self.Health = Health

def attack(self):

self.Health = self.Health - 0.01 * self.Health

return(self.Health)

def dodge(self):

return(self.Health)

def evolve(self):

self.Name = newName

return(self.Name)

object = Pokemon(Pikachu, Electric, 101)

print(object)

Now, we made use of many unknown terms to you which needs to be explained:

- Initializers: The initializer is used to initialize an object of a class. It’s a special method that outlines the steps that are performed when an object of a class is created in the program. It’s used to define and assign values to instance variables.

The initialization method is similar to other methods but has a pre-defined name, init. The initializer is a special method because it does not have a return type. The first parameter of init is self, which is a way to refer to the object being initialized.

The double underscores mean this is a special method that the Python interpreter will treat as a special case. The initializer is automatically called when an object of the class is created.

- Class and Instance Variables: The class variables are shared by all instances or objects of the classes. A change in the class variable will change the value of that property in all the objects of the class. The instance variables are unique to each instance or object of the class. A change in the instance variable will change the value of the property in that specific object only. Let us understand their initializations.

Class variables are initialized outside the initializer and instance variables are defined inside the initializer as follows:

class pokemonVillians: teamName = 'Rocket' def __init__(self, Name): self.Name = Name p1 = pokemonVillians("James") print("Name:", p1.name)Class variables are useful when implementing properties that should be common and accessible to all class objects.

- Method Definitions: A method is a group of statements that performs some operations and may or may not return a result. There are three types of methods in Python:

- instance methods

- class methods

- static methods We will discuss instance methods as they are the most used in object-oriented paradigm. Methods act as an interface between a program and the properties of a class in the program.

These methods can either alter the content of the properties or use their values to perform a particular computation. In the aforementioned example, we have the attack(), dodge() and evolve() methods which introduces changes to the properties. Now, there are two important features associated with method declaration in Python.

Return Statement should not have any return type because Python does not support the idea of a data type

Self argument is a pseudo-variable provides a reference to the calling object, that is the object to which the method or property belongs to. If the user does not mention the self as the first argument, the first parameter will be treated for reference to the object.The self argument only needs to be passed in the method definition and not when the method is called.

Method Overloading in Python does not occur explicitly but rather is an implicit process.

Overloading refers to making a method perform different operations based on the nature of its arguments. Let us take an example:

class Pokemon: def __init__(self, Name, Type, Health): self.Name = Name self.Type = Type self.Health = Health # Method Overloading def attack(self, fire, water, electric, ground, psychic, ghost=None): print("fire =", fire) print("water =", water) print("electric =", electric) print("ground =", ground) print("psychic =", psychic) print("ghost = ", ghost) Pikachu = Pokemon() Pikachu.attack(None, None, electric) Horsea = Pokemon() Horsea.attack(None, water) Alakazam = Pokemon() Alakazam.attack(None, None, electric, None, psychic)So, we can understand that method overloading can take place implicity as well based on the number and nature of arguments (signature of the method) passed into the method during invocation. In the above example, Pikachu.attack() will print only electric attacks, while Alakazam.attack() will print electric as well as psychic attacks in the order. You noticed that we used None in the order of arguments while calling attack() method using the object Pikachu, which is to prevent argument mismatch.

Advantages of Method Overloading:

- Overloading saves memory and since it becomes memory efficient, the execution speed increases.

- It makes the code cleaner and readable

- It allows the implementation of Polymorphism which we will discuss later.

Now, let us come to Class and Static Methods.

Class methods are members of the class and hence can be accessed using the class name without creating a class object.

To declare a method as a class method, we use the decorator @classmethod and cls is used to refer to the class just like self is used to refer to the object of the class. Similar to instance methods, class methods also have a default argument as ‘cls’.

class Pokemon:

teamName = "Team Rocket"# class variables

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name # creating instance variables

@classmethod

def getTeamName(cls):

return cls.teamName

print(Pokemon.getTeamName())

Now, we come to static methods. Static methods are methods that are usually limited to class only and not their objects. They have no direct relation to the class variables or instance variables. They are used as utility functions inside the class or when we do not want the inherited classes.

Static methods can be accessed using the class name or the object name.

Let us try them out now! To declare a method as a static method, we use the decorator @staticmethod. It does not use a reference to the object or class, so we do not have to use self or cls. We can pass as many arguments as we want and use this method to perform any function without interfering with the instance or class variables.

class Pokemon:

teamName = 'Team Rocket' # class variables

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name # creating instance variables

@staticmethod

def trap():

print("Yo! You are trapped in the static made by Team Rocket.")

Pikachu = Pokemon('lol, noob, Thunderbolt!')

Pikachu.trap()

Pikachu.trap()

If we execute this, we will get the message “Yo! You are trapped in the static made by Team Rocket.” twice because the static methods do not change class attributes and leave them as it is.

The purpose of static methods is to make use of its own parameters for useful results.

Now, we come to the concept of Access Modifiers.

Access modifiers are tags we can associate with each member to define which parts of the program can access it directly.

- Public attributes are those that be can be accessed inside the class and outside the class.

- Private attributes cannot be accessed directly from outside the class but can be accessed from inside the class.

- Protected properties and methods in other languages can be accessed by classes and their subclasses. Python does not have a hard rule for accessing properties and methods, so it does not have the protected access modifier.

Let us try to understand each of these concepts with an example. By default, all methods in Python are made publicly available. In order to make it private, we need to have it explicitly done by specifying the keyword private along with the declaration.

class Pokemon:

def __init__(self, name, types):

# all properties are public

self.name = name

self.types = types

def displayName(self):

print("Name:", self.name)

Pikachu = Pokemon("Pikachu", "electric")

Pikachu.displayName()

print(Pikachu.types)

Here, when Pikachu object calls the method displayName and can also access the attribute ‘types’ since they are public so we will get an output here. Now, let us try making some things interesting by using the declaration ‘private’. We can make members private using the double underscore __ prefix.

class Pokemon:

def __init__(self, name, types):

self.name = name

self.__types = types # types is a private property

Pikachu = Pokemon("Pikachu", "electric")

print("Name:", Pikachu.name)

print("Type:", Pikachu.__types) # this will cause an error

In this, you will get the following error message

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "main.py", line 9, in <module>

print("Type:", Pikachu.__types) # this will cause an error

AttributeError: 'Pokemon' object has no attribute '__types'

-

In the above example, name is a public property but types is a private property, so it cannot be accessed outside the class.

-

When it is tried to be accessed outside the class, the following error is generated: ‘Pokemon’ object has no attribute ‘__types’

-

To ensure that no one from the outside knows about this private property, the error does not reveal the identity of it. But, we can still access the private members if absolutely necessary by using _

class Pokemon:

def __init__(self, name, types):

self.name = name

self.__types = types # types is a private property

Pikachu = Pokemon("Pikachu", "electric")

print("Name:", Pikachu.name)

print("Type:", Pikachu._Pokemon__types) # this will not cause an error

Data Abstraction

Why we need to hide information? What is the need of it? Let us try to first understand why is it important to hide information with an example. Consider your college library managed by a librarian and the following class can be used to define the library:

class Library:

def __init__(self, bookID, name, username, password):

# all properties are public

self.bookID = bookID

self.name = name

self.__username = username

self.__password = password

def issueBook(self):

print("ID: ", self.bookID)

def returnBook(self):

print("ID: ", self.bookID)

def login(self):

print("Enter username and password")

l1 = Library(2500, "Python 3 by O'Reilly", "Librarian", "Password")

l1.issueBook()

l1.returnBook()

l1.login()

We observe that the login() method does not need access to book name and book ID at all for use but still has access to them. Hence, this can be a potential data leak and we need to implement a concept where the methods can access only those arguments which they actually need for carrying out their execution.

Data Hiding refers to the concept of hiding the inner workings of a class and simply providing an interface through which the outside world can interact with the class without knowing what’s going on inside.

The purpose is to implement classes in such a way that the instances (objects) of these classes should not be able to cause any unauthorized access or change in the original contents of a class. One class does not need to know anything about the underlying algorithms of another class. However, the two can still communicate. It can be implemented with the idea of Data Abstraction and Data Encapsulation.

Data Encapsulation in OOP refers to binding the data and the methods to manipulate that data together in a single unit, that is, class.

It is a good practice to implement the class members or attributes as private in case of implementing encapsulation. These members can be accessed by public methods of the same class and hence, we can use the attributes without knowing their details. The methods used for this are called as “getters” and “setters”.

A getter method allows reading a property’s value.

A setter method allows modifying a property’s value.

Let us implement this in code:

class Pokemon():

def __init__(self, name=None): # defining initializer

self.__name = name

def setPokemon(self, x):

self.__name = x

def getPokemon(self):

return (self.__name)

Electric = Pokemon('Unknown')

print('Before setting:', Electric.getPokemon())

Electric.setPokemon('Pikachu')

print('After setting:', Electric.getPokemon())

Output is as expected that before setting we get Unknown and after setting we get Pikachu!

Before setting: Unknown

After setting: Pikachu

So, we made a class Pokemon where we defined a private property, named __name, which the main code cannot access. Also, note that we have started the name of this private property with __. For this property to interact with any external environment, we have to use the get and set functions. The get function, getPokemon(), returns the value of __name and the setPokemon(x) sets the value of __name equal to the parameter x passed.

However, there is a brief difference between these two ideas as follows (Credits: GeeksforGeeks)-

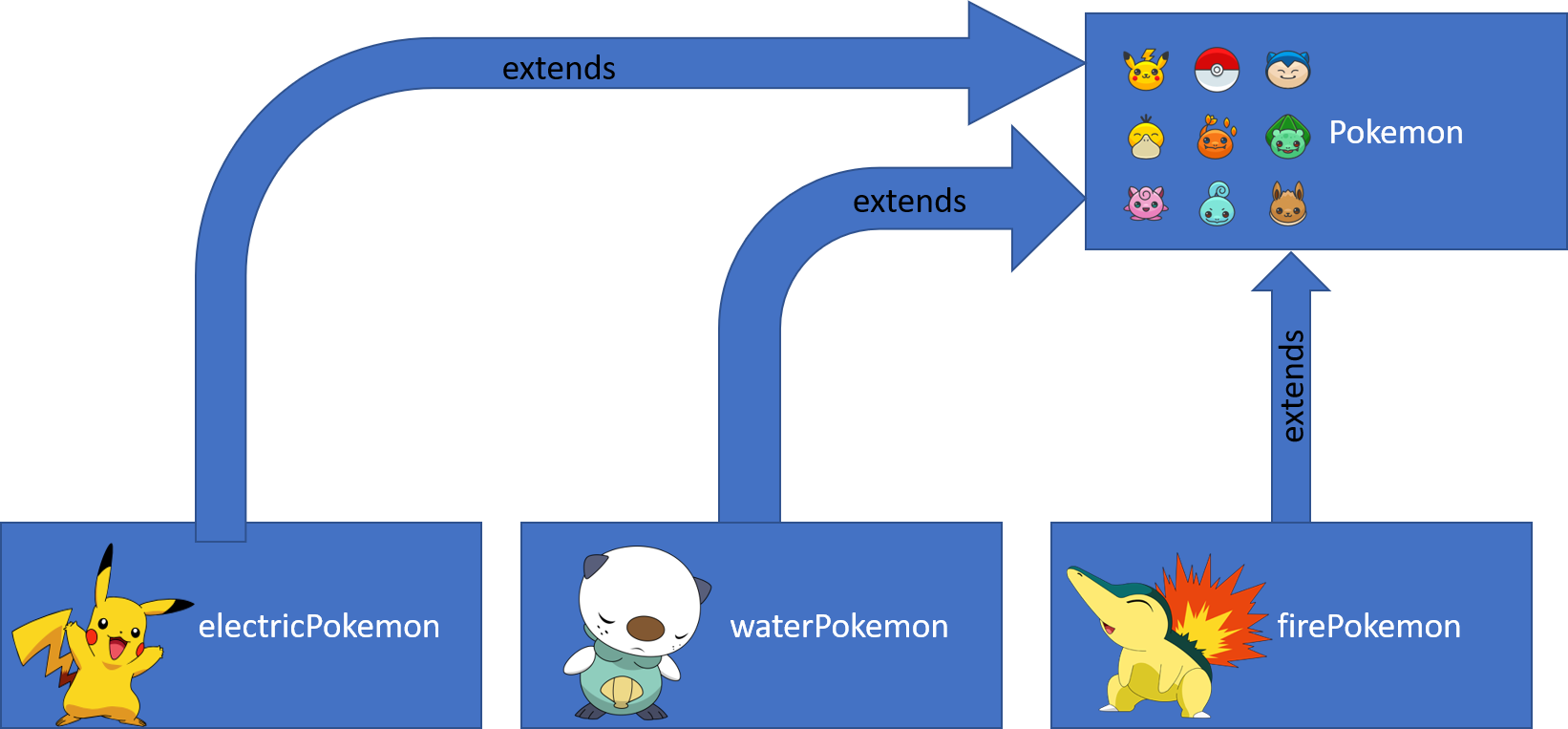

Now, we come to the next principle of OOPs which is Inheritance.

Inheritance

Inheritance is a concept to implement reusability of a class by providing a new way to create classes from existing classes.

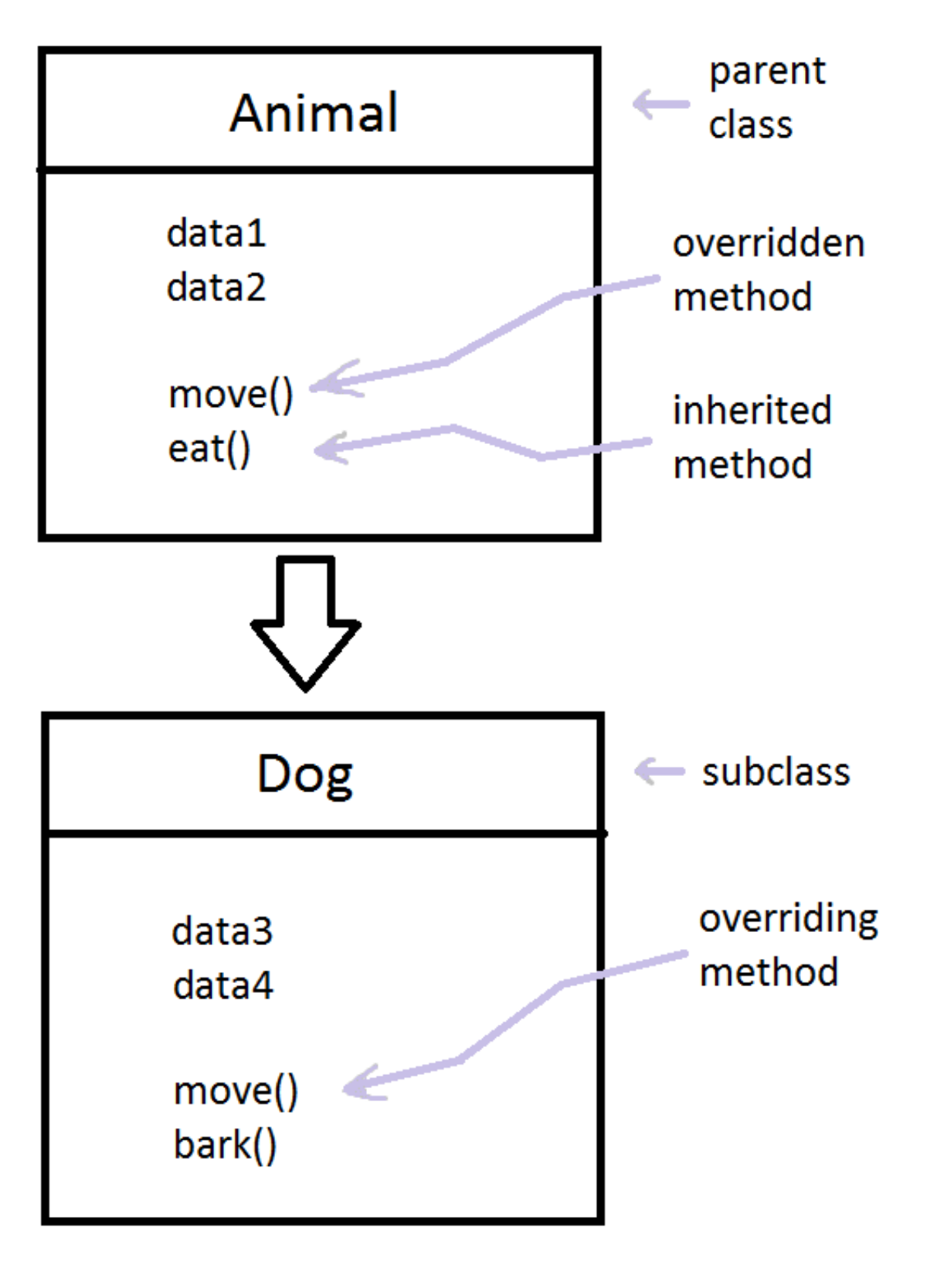

The new class created is called the Child Class and the class from which it inherits all “non-private” variables and methods is called the Parent Class.

Inheritance is a ‘is-a’ relationship that is for example:

We can say that electric type pokemon ‘is-a’ Pokemon, but not all Pokemon are ‘electricPokemon’. Hence, the inheritance relationship can exist in former case but not the latter. In Python, the parent of all the classes is the Object Class, the real OG of Object Oriented Programming.

class Pokemon:

def __init__(self, name, types, health):

self.name = name

self.types = types

self.health = health

def getPokemon(self):

print("Name:", self.name)

print("Type:", self.types)

print("Health:", self.health)

class electricPokemon(Pokemon):

def __init__(self, name, types, health, attack):

# calling the constructor from parent class

Pokemon.__init__(self, name, types, health)

self.attack = attack

def getElectricPokemon(self):

self.getPokemon()

print("Attack:", self.attack)

class waterPokemon(Pokemon):

def __init__(self, name, types, health, attack):

# calling the constructor from parent class

Pokemon.__init__(self, name, types, health)

self.attack = attack

def getWaterPokemon(self):

self.getPokemon()

print("Attack:", self.attack)

class firePokemon(Pokemon):

def __init__(self, name, types, health, attack):

# calling the constructor from parent class

Pokemon.__init__(self, name, types, health)

self.attack = attack

def getFirePokemon(self):

self.getPokemon()

print("Attack:", self.attack)

p1 = electricPokemon("Pikachu", "Electric", "200 HP", "Thunderbolt")

p1.getElectricPokemon()

p2 = waterPokemon("Oshawott", "Water", "350 HP", "Shell Blast")

p2.getWaterPokemon()

p3 = firePokemon("Cyndaquil", "Fire", "400 HP", "Flamethrower")

p3.getFirePokemon()

Hence, we get the output:

Name: Pikachu

Type: Electric

Health: 200 HP

Attack: Thunderbolt

Name: Oshawott

Type: Water

Health: 350 HP

Attack: Shell Blast

Name: Cyndaquil

Type: Fire

Health: 400 HP

Attack: Flamethrower

- In the code above, we have defined a parent class, Pokemon, and multiple child classes, electricPokemon, waterPokemon and firePokemon.

- Car inherits all the properties and methods of the Vehicle class and can access and modify them.

super() Function: The use of super() comes into play when we implement inheritance. It is used in a child class to refer to the parent class without explicitly naming it. It makes the code more manageable, and there is no need to know the name of the parent class to access its attributes.

class Pokemon:

Health = 90

class electricPokemon(Pokemon):

Health = 50

def display(self):

print("Health from Pokemon:", super().Health)

print("Health from electric Pokemon:", self.Health)

obj = electricPokemon()

obj.display()

Hence, we get the expected output:

Health from Pokemon: 90

Health from electric Pokemon: 50

super() is also used with the methods. Whenever a parent class and the immediate child class have any methods with the same name, we use super() to access the methods from the parent class inside the child class.

class Pokemon: # defining the parent class

def display(self): # defining diplay method in the parent class

print("I am from the Pokemon Kanto Originals")

class Johto(Pokemon): # defining the child class

# defining diplay method in the parent class

def display(self):

super().display()

print("I am from the Johto Region Pokemon")

obj = Johto() # creating a car object

obj.display()

And we get:

I am from the Pokemon Kanto Originals

I am from the Johto Region Pokemon

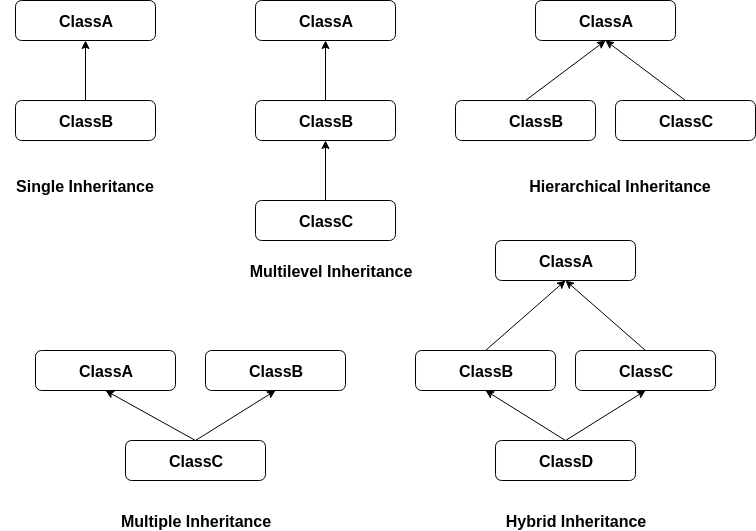

Based on the child-parent relationship, there are five types of inheritance:

- Single Inheritance: In single inheritance, there is only a single class extending from another class. We can take the example of the Pokemon class, as the parent class, and the electricPokemon class, as the child class.

- Multilevel Inheritance: When a class is derived from a class which itself is derived from another class, it’s called Multilevel Inheritance. We can extend the classes to as many levels as we want to.

- Hierarchial Inheritance: When more than one class inherits from the same class, it’s referred to as hierarchical inheritance. In hierarchical inheritance, more than one class extends, as per the requirement of the design, from the same base class. The common attributes of these child classes are implemented inside the base class.

- Multiple Inheritance: When a class is derived from more than one base class, i.e., when a class has more than one immediate parent class, it is called Multiple Inheritance.

- Hybrid Inheritance: A type of inheritance which is a combination of Multiple and Multi-level inheritance is called hybrid inheritance.

Note: Java does not allow all types of inheritance, this is exclusive to Python and some other languages.

Note: Java does not allow all types of inheritance, this is exclusive to Python and some other languages.

Advantages of Inheritance:

- Code Reusability

- Code Modification becomes easy and more localized and you do not have to manually make changes in every class working with common attributes in case of changes.

- Extensibility: Using inheritance, one can extend the base class as per the requirements of the derived class. It provides an easy way to upgrade or enhance specific parts of a product without changing the core attributes. An existing class can act as a base class from which a new class with upgraded features can be derived.

- It is used to effectively implement Data Hiding.

Coming to the next principle of OOPs now!

Polymorphism

The word Polymorphism is a combination of two Greek words, Poly meaning many and Morph meaning forms. Polymorphism refers to the same object exhibiting different forms and behaviors. For example, take the Shape Class. The exact shape you choose can be anything. It can be a rectangle, a circle, a polygon or a diamond. So, these are all shapes, but their properties are different. This is called Polymorphism. Consider the following example of class Shape, which can be used to draw a Circle, a Rectangle and even a Square but with the common method of draw() extended from the parent class Shape.

In effect, polymorphism cuts down the work of the developer. When the time comes to create more specific subclasses with certain unique attributes and behaviors, the developer can alter the code in the particular portions where the responses differ. All other pieces of the code can be left untouched.

class Rectangle():

# initializer

def __init__(self, width=0, height=0):

self.width = width

self.height = height

self.sides = 4

# method to calculate Area

def getArea(self):

return (self.width * self.height)

class Circle():

# initializer

def __init__(self, radius=0):

self.radius = radius

self.sides = 0

# method to calculate Area

def getArea(self):

return (self.radius * self.radius * 3.142)

shapes = [Rectangle(25, 30), Circle(20)]

print("Sides of a rectangle are", str(shapes[0].sides))

print("Area of rectangle is:", str(shapes[0].getArea()))

Here, we get:

Sides of a rectangle are 4

Area of rectangle is: 750

Sides of a circle are 0

Area of circle is: 1256.8

The getArea() method has the same name but different implementations for distinct corresponding classes and gives the output accordingly. Thus, we implemented polymorphism.

We can also make use of inheritance to achieve polymorphism. For that, we will learn a new concept called method overriding. Consider the same code but with inheritance:

class Shape:

def __init__(self): # initializing sides of all shapes to 0

self.sides = 0

def getArea(self):

pass

class Rectangle(Shape): # derived form Shape class

# initializer

def __init__(self, width=0, height=0):

self.width = width

self.height = height

self.sides = 4

# method to calculate Area

def getArea(self):

return (self.width * self.height)

class Circle(Shape): # derived form Shape class

# initializer

def __init__(self, radius=0):

self.radius = radius

# method to calculate Area

def getArea(self):

return (self.radius * self.radius * 3.142)

shapes = [Rectangle(25, 30), Circle(20)]

print("Sides of a rectangle are", str(shapes[0].sides))

print("Area of rectangle is:", str(shapes[0].getArea()))

Method overriding is the process of redefining a parent class’s method in a subclass.

We over-ridden the getArea() method in the aforementioned example.

Advantages of Method Overriding:

-

The derived classes can give their own specific implementations to inherited methods without modifying the parent class methods.

-

For any method, a child class can use the implementation in the parent class or make its own implementation.

-

Method Overriding needs inheritance and there should be at least one derived class to implement it.

-

The method in the derived classes usually have a different implementation from one another.

Next, we will also learn about overloading operators in Python. Operators in Python can be overloaded to operate in a certain user-defined way. Whenever an operator is used in Python, its corresponding method is invoked to perform its predefined function. For example, when the + operator is called, it invokes the special function, add, in Python, but this operator acts differently for different data types. For example, the + operator adds the numbers when it is used between two int data types and merges two strings when it used between string data types.

The last concept used for implementing polymorphism is Duck Typing. We say that if an object quacks like a duck, swims like a duck, eats like a duck or in short, acts like a duck, that object is a duck.

Dynamic typing means we can change the type of an object later in the code.

Duck typing extends the concept of dynamic typing in Python.

x = 5 # type of x is an integer

print(type(x))

x = "Pokemon" # type x is now string

print(type(x))

Hence, Python allows dynamic changing of type during coding.

Let us try this out!

class Pikachu:

def Voice(self):

print("Pika Pika")

class Bulbasaur:

def Voice(self):

print("Bulba Bulba")

class Charizard:

def Sound(self, flame):

flame.Voice()

sound = Charizard()

grass = Bulbasaur()

electric = Pikachu()

sound.Sound(grass)

sound.Sound(electric)

The voice is determined when the method is called, so it does not matter which object type you are passing as a parameter in the Sound() method, what matters is that the Voice() method should be defined in all the classes whose objects are passed in the Sound() method. So, we get:

Bulba Bulba

Pika Pika

Duck typing is useful as it simplifies the code and the user can implement the functions without worrying about the data type. But this may not be the case all the time. The user might not follow the instructions to implement the necessary steps for duck typing. To cater to this issue, Python introduced the concept of Abstract Base Classes, or ABC.

Abstract base classes define a set of methods and properties that a class must implement in order to be considered a duck-type instance of that class.

class Shape: # Shape is a child class of ABC

def area(self):

pass

def perimeter(self):

pass

class Square(Shape):

def __init__(self, length):

self.length = length

def area(self):

return (self.length * self.length)

def perimeter(self):

return (4 * self.length)

shape = Shape()

square = Square(20)

In the example above, you can see that an instance of Shape can be created even though an object from this class cannot stand on its own. Square class, which is the child class of Shape, actually implements the methods, area() and perimeter(), of the Shape class. Shape class should provide a blueprint for its child classes to implement methods in it. To prevent the user from making a Shape class object, we use abstract base classes.

To define an abstract base class, we use the abc module. The abstract base class is inherited from the built-in ABC class. We have to use the decorator @abstractmethod above the method that we want to declare as an abstract method. Now, we will learn about the relationship between objects themseleves.

Aggregation and Composition

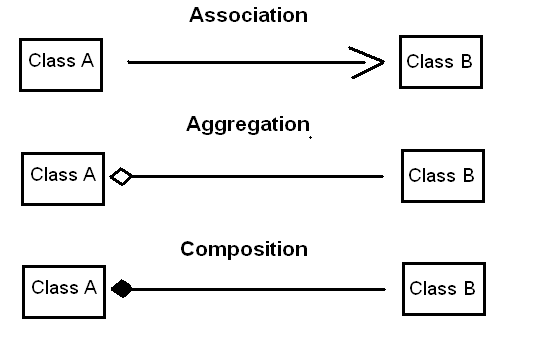

Classes have three different types of relationships. These includes ‘is-a’, ‘has-a’ and ‘part-of’ relatiobships. We already revisited the ‘is-a’ relationship in form of inheritance. We define the ‘Part-Of’ relationship now: In this relationship, one class object is a component of another class object. Given two classes, class A and class B, they are in a part-of relation if a class A object is a part of class B object, or vice-versa.

An instance of the component class can only be created inside the main class. In the example to the right, class B and class C have their own implementations, but their objects are only created once a class A object is created. Hence, part-of is a dependent relationship.

Now, we define the ‘Has-a’ relationship: This is a slightly less concrete relationship between two classes. Class A and class B have a has-a relationship if one or both need the other’s object to perform an operation, but both class objects can exist independently of each other.

This implies that a class has-a reference to an object of the other class but does not decide the lifetime of the other class’s referenced object.

These are formally called Aggregation and Composition.

Let us try to see this in code:

class Car:

def __init__(self, model, color):

self.model = model

self.color = color

def printDetails(self):

print("Model:", self.model)

print("Color:", self.color)

class SmallEngine:

def start(self):

print("Car has started.")

def stop(self):

print("Car has stopped.")

class Small(Car):

def __init__(self, model, color):

super().__init__(model, color)

self.engine = SmallEngine()

def setStart(self):

self.engine.start()

def setStop(self):

self.engine.stop()

car1 = Small("Maruti", "Blue")

car1.setStart()

car1.printDetails()

car1.setStop()

Output:

Car has started.

Model: Maruti

Color: Blue

Car has stopped.

Hence, we come to the conclusion of all the basic object oriented principles. This later transforms to object oriented designing used in the industry. Thus, now, you can write efficient code and also make sure to be a real SUDO user!